Theory

Understanding the Intention-Behavior Gap

The intention-behavior gap (IBG) is a fundamental challenge in health psychology. It refers to the disconnect between what people intend to do and what they actually end up doing. For example, many of us plan to exercise three times a week, but by the end of the week, we find we have only managed one session or none at all. This common gap between our intentions and actions highlights a significant issue in translating plans into behaviors. Despite our best intentions to exercise regularly, eat healthier, or manage stress better, we often find ourselves falling short. This gap reveals that intention alone is not always sufficient to produce action. Understanding this gap can help us bridge the divide between setting goals and making meaningful, sustained changes in our lives.

Why the Intention-Behavior Gap Matters

The IBG is crucial because it directly affects our health outcomes. Many chronic health conditions—such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and obesity—are linked to behaviors that we struggle to maintain despite good intentions. By understanding why the gap exists, we can design better strategies, interventions, and tools to transform our intentions into lasting behavior change. This understanding can empower us to create healthier routines and, ultimately, improve our overall well-being.

The Dynamic Nature of Intentions as the Key to Understanding the IBG

To understand the intention-behavior gap, we must first appreciate the dynamic nature of intentions. Intentions are not static; they change as our life circumstances change. Whether it is due to shifts in our work schedule, unexpected events, changes in our emotional state, or evolving priorities, intentions are inherently flexible. This dynamic quality is both a strength—allowing us to adapt – and a challenge – making it difficult to consistently translate intentions into actions.

One critical aspect of this dynamic nature is the temporal stability of intentions. Intentions that remain stable over time are more likely to lead to successful behavior enactment. However, when intentions fluctuate, the likelihood of following through decreases significantly. This instability often explains why our behavior deviates from our original plans. Therefore, understanding and enhancing the stability of intentions is a key part of bridging the intention-behavior gap.

Another important consideration is the proximity of intention and behavior. The closer in time an intention is to the actual behavior, the more likely it is that the behavior will occur. Intentions formed for actions that are to be taken in the near future are often more stable and actionable compared to those intended for distant future behaviors. This proximity effect means that short-term intentions, with a clear, immediate timeframe, are often more successful than long-term, abstract goals.

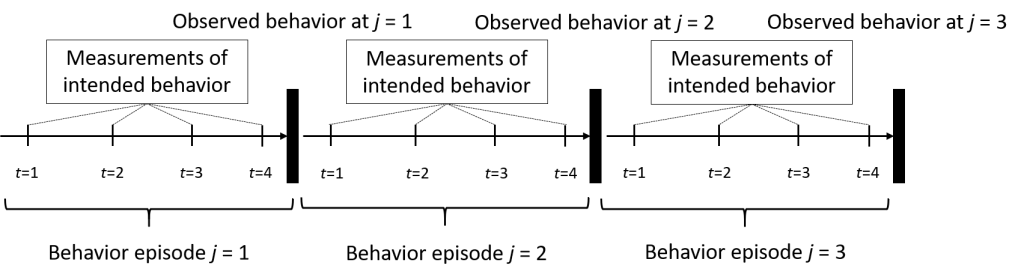

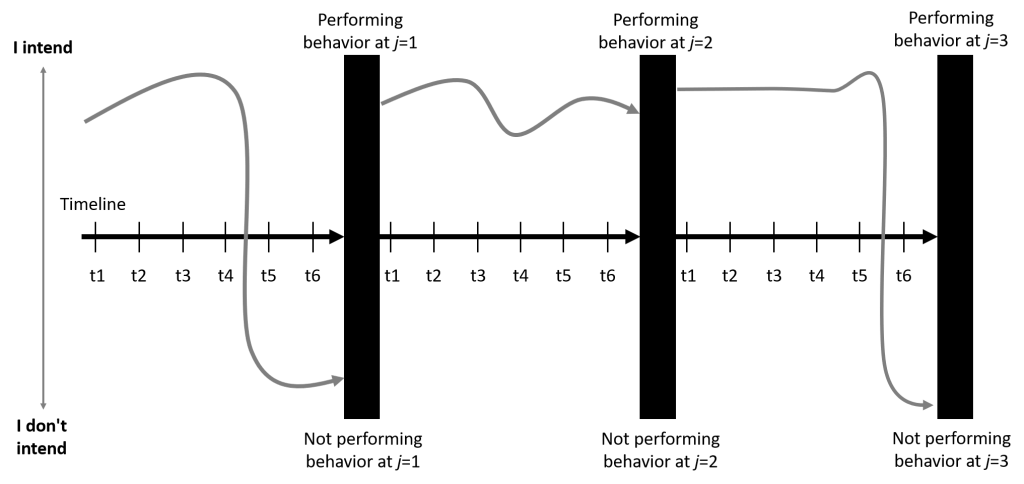

To better understand this concept, consider Figure 1, which illustrates three behavioral episodes for a periodic behavior (e.g., attending a weekly training course). Figure 1 provides a visual representation of how intentions develop and change over time in relation to the intended behavior.

First Behavioral Episode: Initially, the intention to attend the training session is very high, starting 7 days before the session. This high intention remains relatively stable for the next four days, but then drops off about three days before the training. In the last two days before the session, the intention is no longer present, indicating that the person has decided not to attend. Whether or not we observe an intention-behavior gap depends on when we measure the intention. If we measure it 4-7 days before the behavior, we observe a gap, as the intention was high at that point. However, if we measure the intention 1-2 days before the behavior, there is no gap—the individual’s actions align with their latest intentions.

Second Behavioral Episode: In this episode, the intention remains stable at a high level throughout the week. Regardless of when the intention is measured during the week, the outcome is the same: the person acts in line with their intention, and no intention-behavior gap is observed.

Third Behavioral Episode: Initially, the intention to attend the training is stable. However, one day before the actual behavior, the individual changes their mind and decides not to attend. In this scenario, an intention-behavior gap exists during the first five days of the episode. However, if the intention is measured one day before the behavior—or on the day itself—there is no gap, as the action aligns with the updated intention. In this sense, both the timing of the intention measurement and the stability of the intention are crucial parameters influencing the existence of the intention-behavior gap.

Figure 1: Development of intention in three behavioral episodes

Figure 1 illustrates the development of intentions over time across three distinct behavioral episodes, demonstrating how temporal stability, fluctuations, and proximity influence the intention-behavior gap. This visual representation provides a clearer understanding of how the dynamic nature of intentions impacts whether or not an individual follows through with their intended behavior. These insights highlight the importance of both the timing of intention formation and the subsequent stability of these intentions. By examining behavioral episodes in this way, researchers and practitioners can better identify the key factors that facilitate or hinder successful behavior enactment.

The Mathematical Representation of IBG

IBG represents the deviation between our intended behavior and our actual behavior and can be represented mathematically as:

IBG = I – B

Where:

- I = Intended behavior

- B = Observed (actual) behavior

This formula seems very simple and obvious, but it represents a radical departure from traditional ideas of IBG, which see it as a lack of correlation between intention and behavior. This redefinition of the IBG formula has serious implications for the methodology, study designs, and statistics used for the analysis of IBG. For example, study designs may need to shift from between-person analyses to within-person analyses to better capture the dynamic, individual-level variations in intention and behavior.

Four Dimensions of the Intention-Behavior Gap

Exploring the IBG means recognizing that our behaviors are influenced by multiple factors across four key dimensions: persons, time, context, and types of behavior.

- Persons: This dimension reflects the inter-individual differences shaped by personality, motivation, and cognitive processes.

- Time: The time dimension captures how intentions and behaviors can change over different timeframes, highlighting intra-individual variability.

- Context: The context dimension considers the influence of different settings, such as work, home, or social environments, on the translation of intention into behavior.

- Types of Behavior: This dimension refers to variations in IBG across different actions, such as exercising versus dietary choices, even within the same individual.

By addressing these four dimensions, we can better understand what keeps us from achieving our goals and, more importantly, how to overcome those barriers effectively.